Mostrati

1

-

9

di

18

elementi

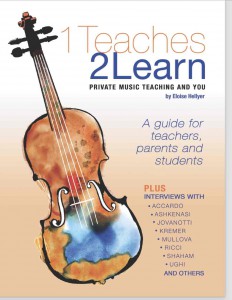

Buy it on www.sharmusic.com - eBook format, avaliable worldwide, paperback in North America

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT

A music teacher’s thoughts and observations on the teaching and the study of a musical instrument, hoping to be of help to parents, students and teachers.

PHOTO

AWARDED TOP 25 VIOLIN BLOG

CATEGORIES

TAGS

ARCHIVES

-

Agosto 2022

Agosto 2023

Agosto 2024

April 2015

April 2016

April 2017

April 2019

April 2020

Aprile 2022

Aprile 2023

Aprile 2024

August 2014

August 2015

August 2016

August 2017

August 2018

August 2019

August 2021

December 2014

December 2015

December 2016

December 2017

December 2018

December 2019

December 2020

Dicembre 2022

Dicembre 2023

Dicembre 2024

Febbraio 2022

Febbraio 2023

Febbraio 2024

February 2015

February 2016

February 2018

February 2019

February 2020

February 2021

Gennaio 2022

Gennaio 2023

Gennaio 2024

Giugno 2022

Giugno 2022

Giugno 2023

Giugno 2024

January 2015

January 2016

January 2017

January 2018

January 2019

January 2020

July 2015

July 2017

July 2019

June 2016

June 2017

June 2018

June 2019

June 2020

June 2021

Luglio 2022

Luglio 2023

Luglio 2024

Maggio 2022

Maggio 2023

Maggio 2024

March 2015

March 2016

March 2017

March 2018

March 2019

March 2020

March 2021

Marzo 2022

Marzo 2023

Marzo 2024

May 2015

May 2016

May 2018

May 2019

May 2020

November 2014

November 2015

November 2016

November 2017

November 2018

November 2019

November 2021

Novembre 2022

Novembre 2023

Novembre 2024

October 2014

October 2015

October 2017

October 2018

October 2019

October 2020

October 2021

Ottobre 2022

Ottobre 2023

Ottobre 2024

September 2014

September 2015

September 2016

September 2018

September 2019

September 2020

September 2021

Settembre 2022

Settembre 2023

Settembre 2024

RECENT POSTS

Who Gets to Decide Who Plays the Violin?

Faith – or Yet Another Reason Why Playing the Violin is Important

Why We Should Take Children to Concerts, Part 2

Why We Should Take Children To Concerts, Part 1

Widening the Circle

Too Smart for Their Own Good

Knowing What You Want (my secret weapon) and Keeping It All in Balance

Slow Progress: Finding Balance, part 4

Realizzato con VelociBuilder - Another Project By: Marketing:Start! - Privacy Policy